Today (September 7th) marks what would have been Buddy Holly‘s 86th birthday. Holly, who would die tragically on February 3rd, 1959, at the age of 22 in plane crash with Ritchie Valens and J.P. “Big Bopper” Richardson, was arguably rock n’ roll’s first singer-songwriter. Holly’s death while on tour with the 1959 Winter Dance Party remains one of music’s greatest losses.

Holly’s hit singles and album tracks, both with and without his backing band the Crickets, such as “That’ll Be The Day,” “Peggy Sue,” “Rave On,” “Maybe Baby,” “Oh Boy!,” “Think It Over,” “Well . . . Alright,” “Rave On,” “Everyday,” “True Love Ways,” “Heart Beat,” and “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore,” inspired a generation of acts including Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, the Searchers, the Who, the Hollies, who named themselves in tribute to him, and most importantly, the Beatles.

Mick Jagger explained Buddy Holly’s influence on all the future British Invasion rockers: “Every English person you talk to, from my generation, at least, will tell you that Buddy Holly was — he was a big influence as a songwriter. And he wrote all these songs in a very short period of time, and they’re all very simple. And he was very big in England, I think he toured only once; I saw him on stage. But he was a very big influence.”

Paul McCartney has without a doubt been the biggest champion for Buddy Holly’s music over the decades: “It’s great music, Buddy’s. It’s very evocative for those of us who were around then. Y’know, it really sums up the period. And a lot of it still plays now, still sounds good.”

McCartney recalled that apart from songwriting, Buddy Holly actually inspired him and John Lennon in other ways: “The thing about Buddy was, whereas Elvis (Presley) was this unattainable, gorgeous, god; Buddy was the boy next door. And I remember John being particularly pleased — he could now put his glasses on. ‘Cause John had big horn-rimmed glasses that he always had to take off when we played or when there were girls around. John, of course couldn’t see a bloody thing — he really was very short-sighted — so, he was very pleased when Buddy came around, ’cause he (could) actually put his horn-rims on and felt like a dude.”

One of McCartney’s first major publishing acquisitions for his company MPL Communications was the Buddy Holly catalogue. Although McCartney has been outspoken regarding the use of his Beatles songs in advertisements and movies, he admits that its a slippery slope for him when dealing with Buddy’s legendary tunes: “It really is very difficult. With the Buddy Holly stuff I do have the right to sort of let people use it, ’cause we’re the publishers of that, we can do it. So I think, generally, I don’t like it — particularly with the Beatles stuff. I don’t know, there might be people out there who say that you shouldn’t do it with Buddy. I don’t know, I’ve done it once or twice with him, but I don’t really like doing it, I must admit. But you get your advisers saying, ‘Okay, so you’re going to turn down all that money, are you?’ It’s a very difficult decision, y’know? If I was being purist, I’d say, ‘No one should do it.’ I mean, my heart says that, but, y’know, you’re not always as pure as you think.”

While accepting his 1998 Album Of The Year Grammy for Time Out Of Mind, Bob Dylan spoke about Buddy: “And I just wanted to say that one time when I was 16 or 17-years-old, I went to see Buddy Holly play, and I was three feet away from him. And he looked at me. I just have some kind of feeling that he was I don’t know how or why, but, I know he was with us all the time we were making this record in some kind of way.”

Keith Richards recalled that Buddy Holly was the prototype for the rock musician who could write, record, and perform their own material: “The beauty of Buddy’s thing to me is the self-containedness of it all. He didn’t need anybody else, he didn’t need, y’know, songs, but just put it all together. He had a great band — God knows how he got it together, but he was the first one to do it. I mean, until the Beatles turned up and Bob Dylan, who strengthened, y’know, writing your own material, nobody was in that position — Elvis (Presley) hardly wrote a song in his life. Jerry Lee Lewis has written one, all the other guys didn’t do it. And it was in that respect, Buddy was streets ahead of his time.”

We asked Graham Nash what he made of Holly upon first hearing him in 1957: “Unbelievable. He was one of us, he was a rock star that had glasses. It wasn’t a sex thing, y’know, like Elvis (Presley) was with his swiveling hips. Buddy Holly touched people’s hearts in how simple his music was and how attainable it was for everybody. I mean, who doesn’t know a Buddy Holly song? I was looking the other day at The Rolling Stone 500 Best Songs Of All Time and he’s got four of them in there! We called ourselves the Hollies for God sake. And he definitely without question influenced the Beatles.”

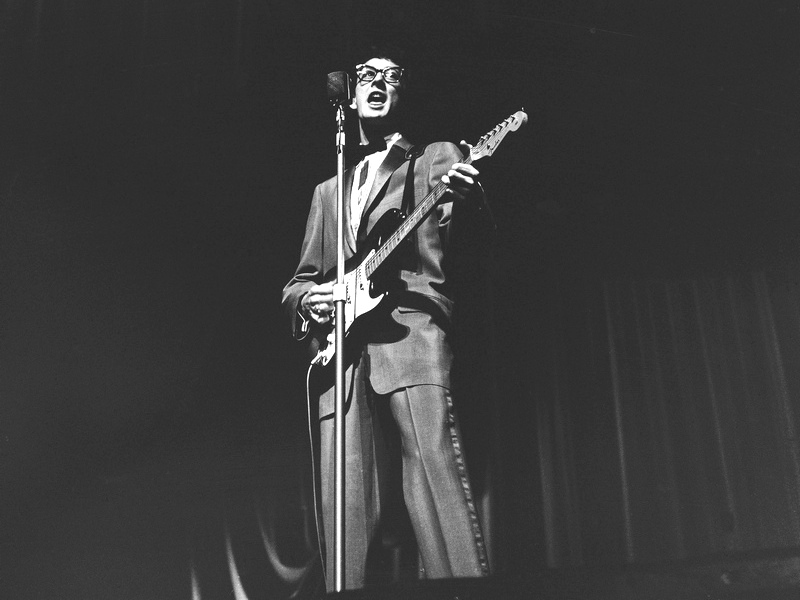

Holly’s trademark Fender Stratocaster sound, with his lean and economical solos, was a pivotal inspiration to the soon-to-be burgeoning West Coast surf sound.

His decision to not only wear glasses but to overstate the fact, by adopting jet-black horned-rimmed glasses, inspired a legion of budding musicians to pick up instruments regardless of their looks.

The Everly Brothers frequently hit the road with the other forefathers of rock n’ roll, and both Don and Phil Everly struck up an immediate and close relationship with Buddy Holly. The late-Phil Everly, who was a pallbearer at Holly’s funeral in 1959, recalled the scene of rock’s earliest tours in an upcoming documentary called Inventing Rock N’ Roll, produced by Everly Films: “The first time I met Buddy Holly was. . . Don and I joined a big package tour, y’know. . . I believe it was the Fats Domino tour. Everybody was on it — it was something. And, what it was, everybody was down in the, like, locker rooms, like at a sports event y’know, with a — everybody had a hook (laughs), y’know, for your wardrobe, and we all sat on benches and we were all in the same room and that’s when we first met him. I was 18 at the time, so it was like going to college. Everybody was a contemporary and all that. It was like being in a fraternity (laughs), it was really, really something. We rode buses together on the tour and just was the best of. . . I always call it the golden age of rock.”

Dion DiMucci, who along with the Belmonts was fourth on the bill of the 1959 Winter Dance Party, told us that despite Holly’s humble Texas upbringing, he seemed wise beyond his years: “I spent two weeks with him. And he was very mature for his age. I mean, I was 19 — he was 22. He was a very decisive guy. I don’t know if it was his upbringing, but I couldn’t make decisions that fast. I mean. . . Well, he rented a plane! At 22 years-old, ‘Okay, listen’ — Y’know he was recruiting people — ‘Let’s fly out and we’ll just split it.’ But you think of a 22-year-old chartering a plane, that was his kind of personality.”

According to several sources, including the late country legend Waylon Jennings, who was playing bass for Holly on his final tour, Holly’s post-tour plans were to reconvene with the Crickets — drummer Jerry “J.I.” Allison and bassist Joe B. Mauldin — and carry on with current sideman Tommy Allsup on lead guitar. Holly was also planning on starting his own record label — Prism Records — and signing Jennings as its first artist. Not long before his death this past August 22nd at age 82, J.I. Allison recalled the deal that he and Holly made prior to him moving to New York City in 1958: “The last time I saw Buddy as a matter of fact he said, ‘O.K., if you’re not gonna move to New York, y’all just work as ‘the Crickets’ and I’ll work as ‘Buddy Holly’ and if it doesn’t work out for either one of us we’ll get back together, okay?’ And we said ‘Fine.’ And Waylon told me that Buddy was talking to him on that last tour and said ‘I’m going to get J.I. and Joe B. back.’”

Holly’s widow, Maria Elena, who miscarried their child shortly after his death, recalls their time living in New York City as being an eye-opener for him as he explored the Greenwich Village folk scene and jammed most mornings with musicians at Washington Square Park, which was practically right outside his apartment building the Brevoort: “He really liked the excitement, and at that time that’s where — as they say, where the action was. New York at that time was for musicians. On top of that, that’s where I’m from. That’s where the Brevoort is on Fifth Avenue, close to Washington Square Park. And that was something that Buddy really enjoyed, because that’s where he saw that he could start a new career.”

She remembers Buddy performing for free, almost daily, with local musicians at the Park: “Right in the fountain — y’know, they’d have the benches there in the morning. We’d walk to Washington Square Park, and that’s where a lot of musicians congregated. Buddy would sit with a guitar and start playing, and then all of a sudden you see all these people gravitating towards him. They’d say, ‘Are you Buddy Holly — ‘That’ll Be The Day’?’ And then. . . little by little, we did that every day.”

Released in 2011 in celebration of his 75th birthday were two star-studded Buddy Holly tribute albums: The MPL-endorsed Rave On: Buddy Holly and the Peter Asher-produced set, Listen To Me: Buddy Holly. The two albums feature such heavyweights as McCartney, Ringo Starr, Brian Wilson, Stevie Nicks, Jeff Lynne, Graham Nash, Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, Nick Lowe, and Lou Reed paying homage to Buddy.