The legendary 1971 Melody Maker letter from John Lennon to Paul and Linda McCartney is up for action with the sale set for August 19th via the Gotta Have Rock And Roll site. Lennon’s infamous rant is expected to sell for up to $40,000.

The November 24th, 1971 open letter to McCartney was sent to the editors of Britain’s Melody Maker music magazine in response to a McCartney interview published four days earlier.

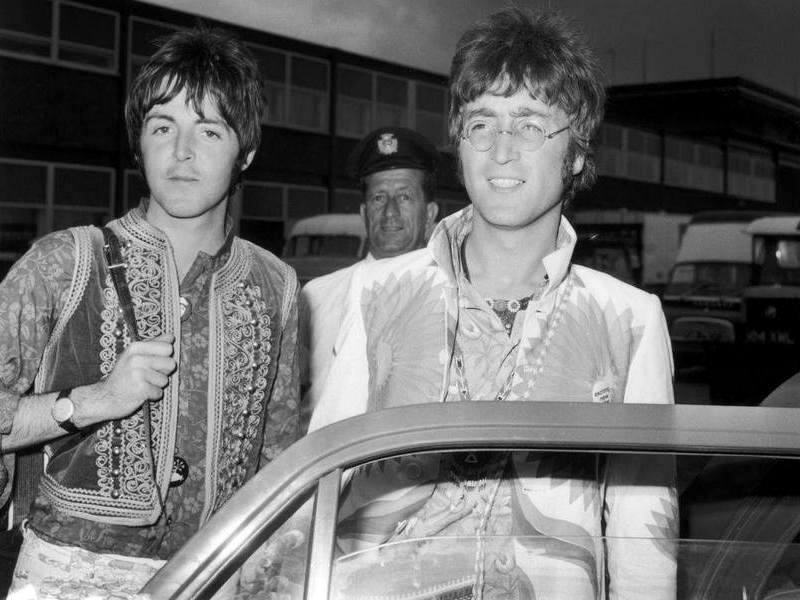

McCartney’s interview — and Lennon’s letter — is based around the battle for control of the Beatles’ Apple empire, which had Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr, along with their collective manager Allen Klein pitted against McCartney, who had wanted Linda’s father and brother — attorneys Lee and John Eastman — to represent the “Fab Four’s” affairs. While at a creative and financial stalemate in December 1970, McCartney sued the former Beatles in an effort to formally end their binding partnerships and put all their earnings into court receivership — for which he was successful.

An enraged Lennon speaks of the Beatles’ split and writes at one point: “If you’re not the aggressor (as you claim), who the hell took us to court and s*** all over us in public? Who was buying up Northern Songs shares behind my back? Even before (Allen) Klein came in! (No excuse) Who’s the guy threatening to ‘finish’ Ringo and Maureen (Starr), who was warning me on the phone two weeks ago? Who said he’d ‘get us’ no matter the cost? — As I’ve said before — have you ever thought that you might possibly be wrong about something?”

Regarding McCartney’s comments on Lennon’s then-recent chart-topping Imagine album, Lennon countered with: “So you think ‘Imagine’ isn’t political, it’s ‘working class here’ with sugar on it for conservatives like yourself!! You obviously didn’t dig the words. Imagine! You took ‘How Do You Sleep’ so literally (read my own review of the album in Crawdaddy). Your politics are very similar to Mary Whitehouse‘s — saying nothing is as loud as saying something!’

He went on to slam his former partner who had previously stated that “John and Yoko are not cool in what they’re doing,” to which Lennon asked, “Wanna put your photo on the label like uncool John and Yoko, do ya? (Ain’t ya got no shame!) If we’re not cool, WHAT DOES THAT MAKE YOU…….”

Lennon calmed down by the end of the letter offering up some type of post-beat down olive branch, statting: “No hard feelings to you either. I know we basically want the same, and as I said on the phone and in this letter, whenever you want to meet, all you have to do is call.”

Paul McCartney says that both fans and the press have nearly always incorrectly pegged him as the villain in the Beatles’ breakup: “Wrong, wrong, sorry. It wasn’t me. It was John. What actually happened was: The group was getting very tense; it was looking like we were breaking up. One day we had a meeting, I came in and it was all Apple and business and Allen Klein and it was getting very hairy and no one was really enjoying themselves. It was. . . we’d forgotten the music bit — it was just business. I came in one day, and I said, ‘I think we should get back on the road — small band, go and do the clubs, sod it, let’s get back to square one, let’s remember what we’re all about. Let’s get back.’ And John’s actual words were, ‘I think you’re daft. And I wasn’t gonna tell ya, I’m breaking the group up.’ He said, ‘It feels good — it feels like a divorce.’ And he just sat there and our jaws just dropped.”

Paul McCartney biographer Christopher Sanford told us that throughout the 1970’s, the Beatles kept close tabs on each other’s respective work — with John Lennon and Paul McCartney never missing an opportunity to pour over and analyze one another’s solo albums thoroughly: “John always critiqued Paul’s albums, either in public or between the two of them. And I found that one of the most poignant aspects of the whole ’70s, y’know, relationship — or non-relationship. They always deconstructed each other’s records. They had to have the latest album immediately shipped to them from the other party. And they would often do these very minute sort of deconstructions of each track.”